Rumi Love Poems Biography

Source(google.com.pk)This review was originally written as a response to a one-star Spotlight Review entitled "Look elsewhere for Rumi's essence", which criticized Barks' versions of Rumi as inauthentic because they are not precisely literal; that negative review has since been removed. But what I said then still goes: Don't let the negative reviews drive you away from a great read. This book captures Rumi's essence like no other. And despite what the critics think, Coleman Barks is very well qualified to bring Rumi to a modern English audience. Consider these four points:

1) First, and most important, Barks loves Rumi; he loves Rumi's poetry; he loves that Presence Rumi's poetry celebrates and explores. In the original criticism, the reviewer implied Sufi poetry employs some kind of mantric magic when he said that "their poems are actually precise and carefully constructed technical instruments designed to have very specific effects on the reader under the right circumstances." Please. Rumi himself makes plain throughout his works that the point of his poetry - and of Sufism - is not technique. The point is love: "Rub your eyes, and look again at love, with love." Rumi would have been the last person in the world to insist on strict adherence to technique, or compulsive literal translation. He was about soul, and transformation, and he said over and over again that the only real magic was love. That's the real essence of Rumi. And maybe Barks has been able to translate Rumi's poetry so effectively because he's coming from the heart and the soul, and not just the head.

2) Second, Barks is a well-known American poet in his own right, a retired professor of English at Georgia University. He's studied the life and work of Rumi intensively for over thirty years. And he was a personal student of the great Sufi teacher Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, so he knows something about Sufism and Rumi's "path of love" from direct personal experience.

3) Third, while it is true that Barks does not read Rumi in the original Persian, his modern English versions of Rumi are based on the painstaking study of the best critical English editions of Rumi available, including those of Moyne, Arberry and Nicholson - and if you want to know why Barks chose to go beyond these literal translations and create his own modern versions of Rumi in plain English, try reading a critical edition like Nicholson's - yes, it's a literal translation, and it's very scholarly, but it's almost unreadable. In fact, it's torture. Scholarship is important, but poetry should be a joy.

4) Finally, Barks must know something, because he just got an honorary doctorate from the Department of Persian Language and Literature at the University of Tehran for his translations of Rumi. (Here's the announcement: "The Diploma of Honorary Doctorate of the University of Tehran in the field of Persian Language and Literature will be granted to Professor Coleman Barks, Poet and Professor Emeritus of English, University of Georgia, USA, for translating the poetry of Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi, the great Iranian poet and philosopher at 10:00-12:00 a.m. on Wednesday, May 17, 2006 at Ferdowsi Hall, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Tehran.") And Barks is respected by other modern Iranian-American writers. For instance, on page 286 of his new book "No god but God; the Origins, Evolution and Future of Islam", Reza Aslan - who was born in Iran and now lives in the US - acknowledges that "The best translations of Rumi include Coleman Barks, The Essential Rumi (1995), and the two-volume Mystical Poems of Rumi by A. J. Arberry (1968)..."

There are lots of versions of Rumi out there, including the literal translations like Arberry's or Nicholson's. Barks' obviously respects these literal translations tremendously. They do capture the letter. But Barks frees the spirit. Let me conclude by quoting a wonderful story Barks tells about translating the essence of Rumi's poems. This is from page 180-181 of his new book, "The Soul of Rumi":

Barks writes: "Perhaps presence is so elusive because of those continually disintegrating and reconstituting motions called 'fana' and 'baqa': the wild longing to dissolve in God and then the coming back in the kind hand that reaches to help. That motion is the subject of Rumi's poetry, or it might be better to say that his poetry enjoys the play of presence and absence, through the mind, through desire, love, deep silence, the whole conversational dance of existence, the being of Being. Flowers and fish are doing calligraphy with their moving about. The great sun outside and the sun inside each human hum together. The bright core of their resonance is who we are. I love this Hasidic story about the transmission of such fire:

"When the Baal Shem Tov had difficult work to do, he would go to a certain place in the woods, where he made a fire and meditated. In the spontaneous prayers that came through him then the work that needed to get done was done. A generation later the Maggid of Meseritz was given the same work. He went to the place in the forest and said, "I no longer know how to light the fire and meditate, but I can say the prayers." What needed to happen, happened. A generation after that it came to Moshe Leib of Sassov to do the work. He went into the woods and spoke, "I do not know the fire meditation or the prayers, but I still come to this place where the Baal Shem and the great Maggid came. I hope that's enough." And it was. After another twenty years, Israel of Rishin was called to the task. "I do not know the place, the fire, the meditation, or the prayers but here, inside, sitting at table I can tell the story of how it used to go." The story had the same effect as the wilderness retreat, the fire meditation, and the prayers that came to the Baal Shem Tov, the Maggid, and Rabbi Moshe Leib."

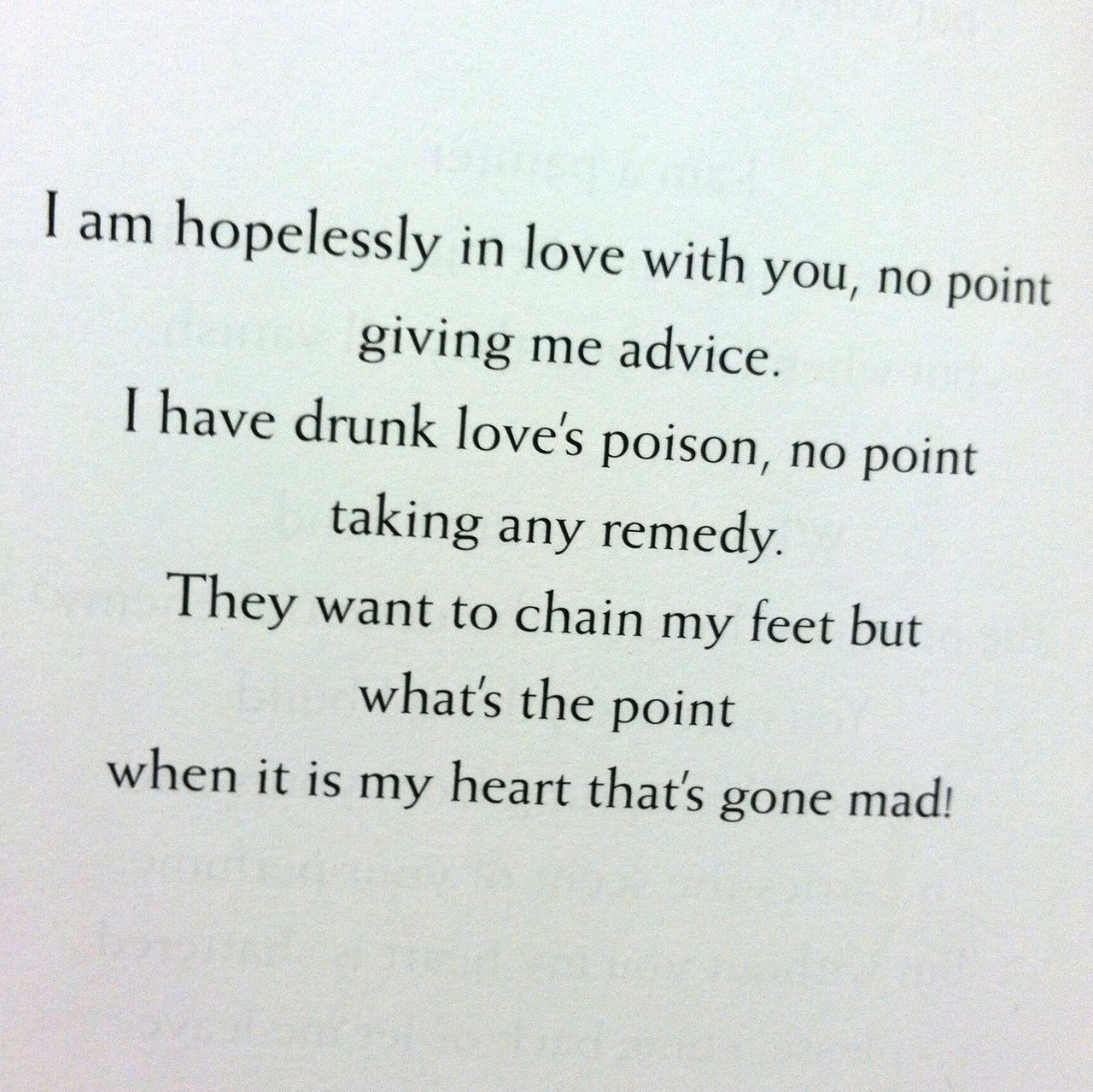

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

Rumi Love Poems

No comments:

Post a Comment